(By Nguyen Quoc Toan with contributions from ChatGPT and DeepDream)

For the successful professional, there is no greater peril than the psychological trap of denial. The most capable individuals often possess the greatest resistance to admitting a problem, mistaking self-reliance for competence.

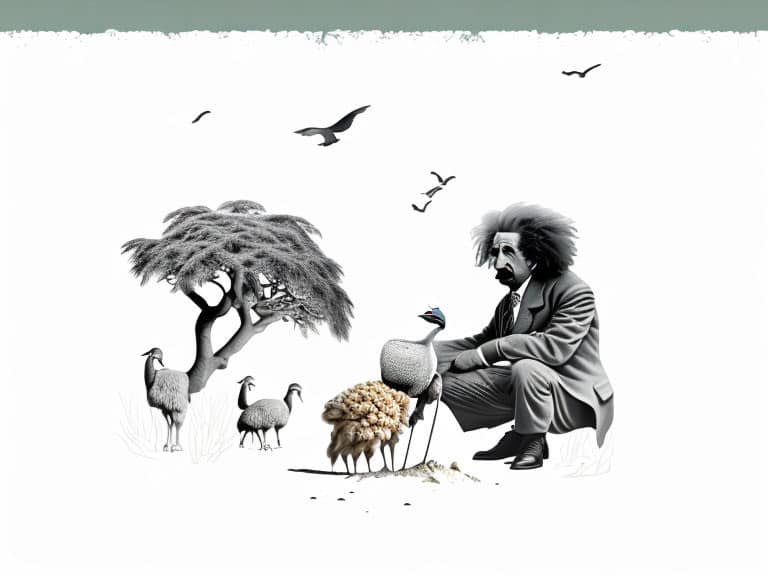

This dangerous convergence is defined by two principles: the Ostrich Effect and Einstein’s definition of insanity—the idea that madness is doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting different results.

Below are three real-life cases, demonstrating how talented professionals fell victim to this cycle of denial and stubborn repetition.

The case of Tam: The blind investor

Tam was a respected financial consultant known for his ability to raise capital and restructure struggling companies. When a promising, but struggling, consumer goods client approached him, Tam took on the project with immense fervor.

He worked endless hours, poured his expertise into rescue plans, and developed a rapport so deep he began using his personal wealth to prop up the business. His partner, Khanh, grew concerned, warning Tam about multiple red flags regarding the client’s reputation and solvency. Yet, Tam was psychologically entangled to the point of blindness. He was determined to prove to his colleagues that he could solve any problem, constantly clashing with Khanh.

Things deteriorated quickly. Despite Tam’s best efforts, the client could not raise capital, its reputation plummeted, and it lost market share. Tam’s home life frayed under the stress of long hours and his personal financial exposure. When the client company finally collapsed, Khanh—unable to endure the conflict—left in anger. Tam’s professional and personal life was nearly destroyed. He and Khanh never recovered their friendship or partnership.

(I was that blind character, Tam, twelve years ago. The following two stories are also entirely true, shared by friends who own industrial companies.)

The case of Thang: The arrogant administrator

In an industrial manufacturing group, Thang was a revered executive, admired for his expertise and decisive nature. He oversaw a major business segment with a team of exceptionally talented subordinates.

With a powerful ego and vast experience, Thang was determined to prove to the Board that he could achieve rapid success with his new plan. He aggressively pursued his strategy, dismissing all dissenting opinions and ignoring the feedback of his team. His decisions, even when countered by evidence, were absolute.

Over time, Thang’s team lost all motivation. Key partners began refusing to work with his division. The market started to slip. Despite desperate warnings from his subordinates, direct superior, and the Board, Thang buried his head in the sand, blindly convinced he could make up the lost revenue by simply doubling down on his existing, failing strategy.

His division crumbled, its morale broken, and revenue collapsed. The Board erupted in fury at his direct superior for excessively shielding him. Thang’s senior staff either resigned or were on the verge of resigning. His reputation and competence were severely diminished.

The case of Thuy: The isolated leader

Thuy was a successful consumer goods leader who had built a division from the ground up. Respected by her staff and valued by the Board, she was considered a rising star and a clear successor.

However, Thuy faced a deep personal difficulty that she hid from everyone. For over two years, she kept the problem secret, determined to solve it alone. As the issue worsened, it began to affect her professional judgment. Instead of seeking help from friends, colleagues, or superiors, Thuy continued to operate in isolated denial. The boundary between her personal and professional life dissolved. In her frantic, isolated attempts to solve her problem, she began making catastrophic errors both at home and at the company.

Thuy was eventually dismissed, losing everything she had built. Her sudden collapse shocked her family and colleagues, who mourned not just her loss but the fact that she had refused to seek help, choosing instead to bury herself deeper and cling to the irrational hope that the old ways would somehow work.

The mandate for leadership humility

The stories of Tam, Thang, and Thuy illustrate various forms of the Ostrich Effect—the human tendency to reject negative information—combined with Einstein’s definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

We constantly fall into this trap by using a single, failing solution, hoping for a different outcome. Tam kept throwing money at a dead business. Thang repeatedly ignored clear operational feedback. Thuy silently clung to an old method of self-reliance for two years.

The Ostrich Effect and Insanity are dangerous traps that lead the most competent, successful individuals down a path of self-destruction and can easily collapse the organizations they lead.

Therefore, leaders must actively seek support when confronting challenges, whether personal or professional. You must acknowledge that your problems will not vanish simply because you bury your head in the sand. You must have the courage to face them and, critically, seek help from friends, family, and superiors as early as possible.

Do not be blind, rigid, or stubbornly attached to a single solution. Always remember: You are not omnipotent. You cannot solve every problem. And you are not weak for seeking help.