PART 1: THE DOMINO EFFECT OF DISTRUST IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

The global investment community is experiencing a crisis of confidence that began in Southeast Asia. eFishery—Indonesia’s aquaculture technology unicorn, once valued at $1.4 billion and backed by giants like SoftBank and Temasek—was embroiled in a massive scandal, inflating revenue by hundreds of millions of USD and reporting profits where there were only losses in 2024.

The fallout from eFishery has activated a wave of profound skepticism. Foreign investors are delaying capital deployment, prolonging due diligence, or entirely suspending operations in the region due to fears of similar fraud. As Justin Hall of Golden Gate Ventures commented, the region’s image has been damaged, forcing even well-performing companies to face scrutiny that makes investors question whether the high risk of investing in Indonesia is still worthwhile.

This epidemic of caution is costing Vietnam severely. According to DealStreetAsia, investment deals in Vietnam hit a record low in 2024. Though Q1 2025 saw a modest increase ($167 million), this pales against the peak quarters of 2021 (nearly $1 billion). Alongside global instability and high prior valuations, the largest contributing factor is the fading confidence in the investment environment and the difficulty of securing an exit.

While the Vietnamese government’s commitment to attracting foreign capital and improving the business environment is consistent and clear, specific actions by some Vietnamese enterprises are catastrophically undermining that commitment. A review of private equity history in Vietnam reveals countless cases where foreign investors become the victim, often actively bullied by their domestic partners. These disputes, broken commitments, and legal ambiguities are now a serious impediment to international capital flow.

PART 2: THE LEGAL ABYSS: CORPORATE SABOTAGE AND FAILED JUSTICE

I have been directly involved in M&A and am currently representing a company that is likely a victim of fraud. The lack of protection for foreign investors manifests in two major forms: corporate sabotage and legal failure.

A. Corporate sabotage and shareholder bullying

- The Physical Eviction: A sovereign wealth fund invested in a major Vietnamese education company (not EQuest). Due to governance conflicts, the relationship soured. At a General Shareholder Meeting, the Chairman physically had the fund’s representative escorted out by security guards. In nations respecting the rule of law, this is unthinkable. But in Vietnam, it happened without consequence. The fund eventually sold its shares at a modest profit, accepting a quiet exit.

- The Reverse Takeover: Between 2012–2014, foreign funds owning nearly half of a publicly listed building materials company (Company A) clashed with management. The conflict peaked when a newly formed company secured the exclusive rights to Company A’s core foreign technology. Stripped of its technology, Company A faced shutdown. The foreign funds capitulated and divested. Ironically, a year later, the “newly formed” company, now controlled by the former chairman and CEO of Company A, bought the controlling stake. The stock price skyrocketed 60 times, but the foreign funds were gone, erased from the boom they financed.

B. International arbitration failures

In cases where conflict reached international arbitration, Vietnam’s legal system has frequently rejected the international rule of law:

- Sojitz vs. Rang Dong: Sojitz (Japan) won a $7.6 million arbitration award at the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC). However, the Vietnamese court initially refused to recognize the ruling. After a 14-month appeal, the ruling was recognized, but the lengthy delay caused the Vietnamese partner, Rang Dong, to face bankruptcy. This illustrated how the local application of law can effectively re-litigate the substance of an international ruling, undermining the very purpose of global arbitration.

- VMG vs. EPAY: Two Korean funds won a $25 million SIAC arbitration against VMG (a Vietnamese company) for breach of contract. In 2023, the Vietnamese court refused to recognize and enforce the award, completely invalidating the international legal process. The funds suffered immense losses, and the case remains unresolved in 2025—a blatant warning that international rulings may not be honored in Vietnam.

C. The criminal gap: Civilianizing fraud

Most alarmingly, there is a trend to “civilianize” criminal acts—intentionally transforming clear signs of fraud and asset misappropriation into lengthy civil disputes to avoid criminal prosecution.

- The Hospital Hostage: An investment partner was defrauded of hundreds of billions of VND meant for land acquisition and hospital construction. The local partner secretly mortgaged the land and project to a bank. The foreign investor found their project held hostage, forced to pay hundreds of billions to redeem the collateral. The case remains unresolved.

- The EQuest case (Hanoi Star): In 2021, EQuest member companies fully paid Ms. Pham Bich Nga to transfer the Hanoi Star School and a new project, with a clear commitment that the finished project would be handed over to EQuest. After EQuest’s funds built the facilities and secured licenses, Ms. Nga unilaterally terminated cooperation, refused the handover, and brazenly retained the full sum. After nearly two years, EQuest has been unable to recover the money or the school.

These cases share a common, terrifying denominator: the domestic partner exploits legal loopholes, pushing the dispute into civil courts to delay justice or completely evade criminal liability. This constitutes a severe threat to Vietnam’s investment climate, signaling that the cost of breach of trust is negligible.

PART 3: THE SOCIAL CAPITAL DRAIN AND THE MANDATE FOR JUSTICE

“Niềm tin còn một chút này / Chẳng cầm cho vững lại dày cho tan” (The little bit of trust that remains / If not held firm, will be trampled and dissolved.)

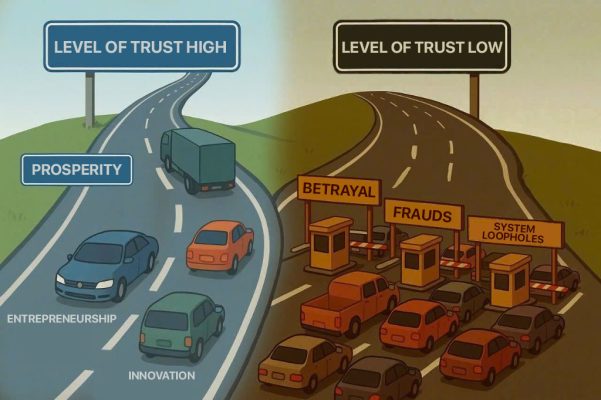

The failure to punish betrayal properly leads to a swift depletion of social capital. In an economy where trust in official institutions wanes, every transaction becomes riskier, more complex, and more expensive. Business is forced to rely on costly, informal “relationships” rather than the rule of law.

Francis Fukuyama, in Trust, argued that nations lacking social capital struggle to develop large enterprises because the lack of trust forces state intervention and raises transaction costs. If Vietnam does not reform its judicial system, it will be pushed into a low-equilibrium trap, where fear of losing principal capital stifles all major investment and innovation.

A. The silence and the cost of capital

- Why funds leave silently: Many funds—especially global ones—avoid public disputes to protect their institutional reputation and access to future limited partners (LPs). They are often politically intimidated into silence, fearing regulatory retaliation. However, the private world of finance talks: the gossip of betrayal and failed trust spreads rapidly.

- The time trap: The typical investment fund lifecycle is 5–7 years. Civil litigation in Vietnam can easily consume 3–5 years, locking up capital in an indefinite legal battle. Funds choose to cut losses and leave rather than engage in a costly, time-consuming war with no guaranteed end.

- The bob test: As a former executive of a billion-dollar fund told me, “In Vietnam, my fund’s profit entirely depended on the grace of the founder, not the contract.” This mentality—the founder acting as if they are granting a favor to the investor—is toxic to a modern economy.

B. The mandate for judicial reform

Vietnam possesses a sound legal framework, but enforcement is weak. Recovery rates are low (25–40% vs. Singapore’s 70–85%), and processing time is slow (24–36 months vs. Singapore’s 12–18 months).

The government must define the protection of investor rights—especially foreign investors—as a strategic national security priority. This requires a comprehensive judicial overhaul:

- Independent Economic Courts: Establish specialized economic courts with judges trained deeply in international commercial law.

- Enforcement of International Norms: Decisions must be fair, transparent, and enforceable quickly, aligning with international standards to prevent the trivialization of international arbitration awards.

- Prioritization: The state must clearly mandate that resolving foreign investment disputes is a high-priority task throughout the administrative and legal system.

To truly build a modern business culture, Vietnam needs a campaign akin to the “Furnace Cleaning” (Đốt Lò)—this time, aimed at cleaning up the investment environment. We must decisively prosecute fraud and breach of trust, protect investors, and secure the foundation of trust. Only then can Vietnam’s economic ambitions truly take flight.

Nguyễn Quốc Toàn

(I would like to thank the journalists, analysts, and lawyers who reviewed, provided information, and gave feedback on this article.)